Vegetation Management for Solar Panel Sites

No matter the type of solar installation or its location, it’s important to manage costs for both development and maintenance of a solar panel. One of the most important factors affecting costs is long-term vegetation maintenance. Land use experts, local ranchers and other experts can help developers make planning decisions that affect long-term use, including controlling vegetation around key components and creating habitats that are hospitable to beneficial species, such as pollinators and native plants. By including experts throughout the development process, and by considering the end land-use goal from the start, solar panel site developers and managers can plan for the long-term success of the site.

Solar farms are becoming a common sight across the country, across all landscapes, from urban to rural. The U.S. solar industry is expected to grow, so land developers and managers will continue to have a significant role to play in its evolution.

Solar requirements differ depending on how the site will be used, location and environment, vegetation or habitat desired and other factors. But no matter the type of solar installation or its location, it’s important to manage costs for both development and maintenance of the site. One of the most important factors affecting costs is long-term vegetation maintenance.

Another challenge developers and managers face is public perception of solar installations, usually concerns about the appearance of sites. Public perception is rarely considered during project planning, meaning budget won’t be allocated. And when it comes to how a solar panel installation will look, vegetation management plays a big role.

When planning a solar development, it’s important to have all the right people at the table making decisions — from the project designer to construction management through to the end user and those in charge of maintaining the surrounding land. Vegetation management decisions can affect project design and cost planning, so there’s a significant value in having these experts involved in planning from the very beginning.

There are many questions to ask when considering the long-term use and management of a solar site. Where is it located and what impact will the terrain and climate have on vegetation? What do you want to grow there, if anything? What kind of habitat is desired? What storm water considerations should be taken into account? While it would be nice to walk away after construction and just let nature take over, the functionality and safety of a solar site can be affected by the surrounding vegetation. Land use experts, local ranchers and other experts can help developers make planning decisions that affect long-term use.

There are three major phases to solar farm projects: pre-construction, engineering procurement and construction, and operation and maintenance. The preconstruction phase, which is typically around three to five years or longer, includes land acquisition, permitting and planning. The construction phase usually lasts about a year. Ongoing maintenance lasts for the duration of the project’s life, so 10 to 15 years and sometimes decades longer. Land managers oversee this final phase.

Each phase has synergies with the others, and involving representatives from each phase in the planning process can help make sure the needs of developers, builders and end users are met and set the stage for long-term maintenance.

Integrated vegetation management (IVM) involves managing plant communities to achieve specified objectives, including selecting and implementing control methods. An IVM strategy should be initiated during the pre-construction phase when you consider the site’s future habitat, panel placement and site layout, ecological needs, regulatory requirements, storm water and drainage, erosion mitigation and other factors. Evaluate the existing site condition for invasive or undesirable vegetation. Will the site need to be mowed prior to construction? Is grading or soil movement needed? Will the site need to be reseeded? Grading or leveling a site will have a major impact on establishing — or reestablishing — your desired habitat.

Sometimes bare ground is optimal, such as where there might be fire risk. But a more aesthetically pleasing site may be preferred. This could include grasses, native plants or a full pollinator or grazing habitat.

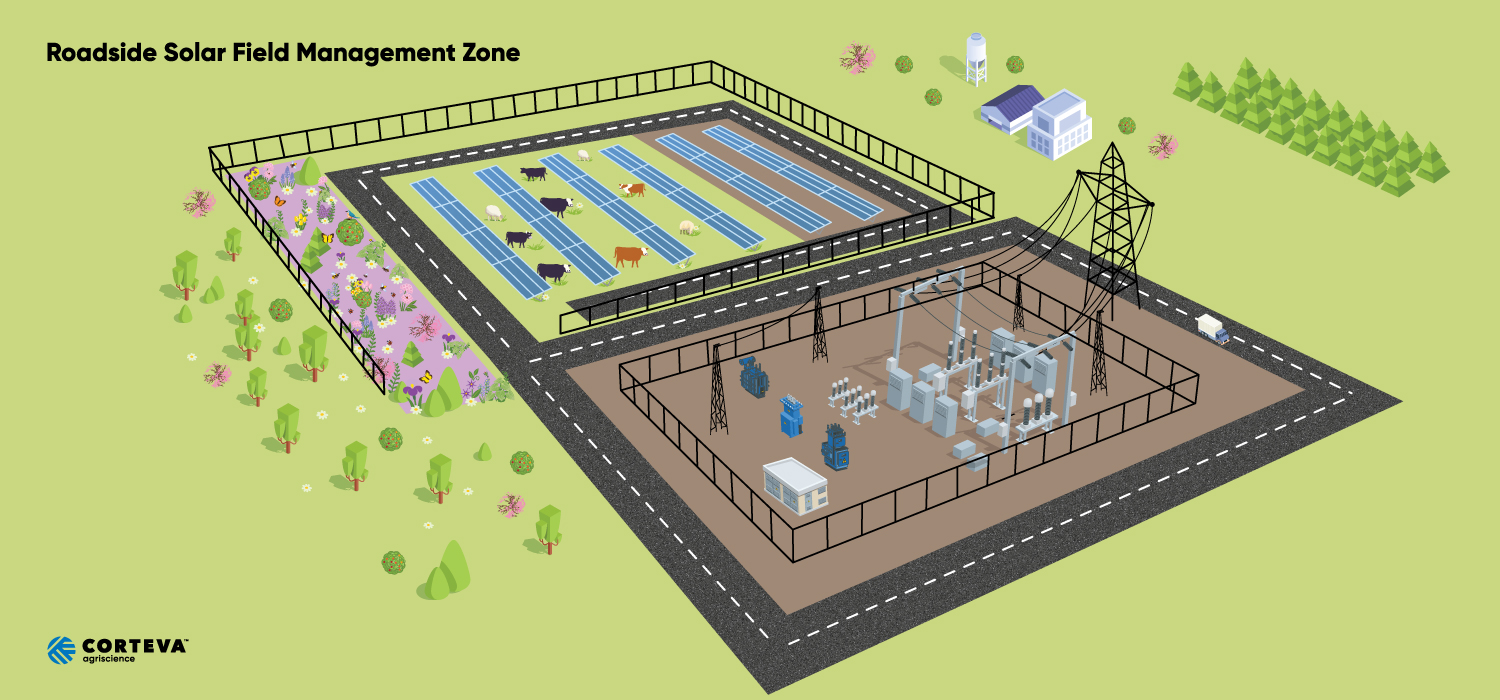

This illustration shows how vegetation at solar panel sites can accommodate various habitats, offering areas for grazing, pollinators and native plants.

It is nearly impossible to develop a site without some soil disruption and compaction. Native species may remain in the existing seedbank, but the land may need help reestablishing the growth of native plants. You may be able to reseed the land before the construction phase even begins. Establishing vegetation before construction costs less and moves development to the operation and maintenance stage more quickly.

Consider which species are desirable for the habitat you’re trying to create, what weeds you’ll need to prevent and how climate and weather might affect maintenance. Evaluating your needs early in the development process can aid decision making and budget allocation. Cultivating native plants — whether from the existing seedbank or by reseeding — can also help reduce costs for long-term IVM.

Total vegetation control is needed under solar panels and around other site infrastructure such as substations, fencing and access roads. Preventing vegetation interference is also important for fire prevention in more arid environments.

When planning for long-term vegetation management after construction, you’ll need to consider whether to mow or use other management practices. Low maintenance doesn’t mean no maintenance, so some control measure will be needed to prevent vegetation interference with panels and maintain access to the site. Options include traditional mechanical mowing, perennial growth regulator treatment (also called a “chemical mow”) and use of targeted herbicides.

Some drawbacks to mechanical mowing include labor and the cost of mowing multiple times per growing season. Mowing can also negatively affect animal habitats — nests and eggs could be disturbed or exposed to predators. And it’s not selective, so when trying to establish a pollinator habitat, mowing could cut off the flowers you need to attract desirable insects.

Instead, selective herbicides or perennial growth regulators (PGR) can be used to manage vegetation areas during the growing season. This is often more costeffective than mechanical mowing because each can offer season-long weed suppression. Herbicide application can be less invasive to developing habitats, and most also have no grazing restrictions.

Keep in mind that treating for one invasive species may give another the opportunity to thrive and you’ll have to treat it later. For example, vegetation management focused on preventing cheatgrass may leave kochia to fill in those gaps and need to be addressed later on.

These photos show various types of vegetation around solar panels — bare ground, low-height clover and grasses, and a pollinator habitat. (Photos courtesy of H2 Enterprises.)

Because there’s no single solution when it comes to managing solar sites — or any industrial site, for that matter — it’s important to take an integrated approach to vegetation management. When using herbicides for management, a general broadcast application works well during the beginning restoration phases. A preemergent herbicide can be used to prevent weeds that could grow above your desired vegetation.

Moving into post-construction long-term maintenance, spot treatment applications may be enough, though some brush may require stump cutting. Selective treatment should be the long-term goal for solar sites. Unfortunately, grading and reseeding can create an ideal environment for invasive or noxious weeds to thrive. A program approach is important for controlling them, with products that will allow for any additional reseeding needed. Herbicides can often be applied directly under the panels and around infrastructure. The goal should be effective herbicide stewardship using the right herbicides at the right rates at the right time to help prevent resistance.

More pollinator habitats mean more pollinator benefits for the environment. Native flowering plants, host plants and nesting sites that are beneficial to bees, butterflies and other pollinators are quite compatible with energy infrastructure. Solar sites are the optimal spaces for pollinator habitats since they’re rarely disrupted. Plus, these habitats help promote favorable public perception of solar installations.

One way to evaluate the viability of a space as a pollinator habitat is by using the Pollinator Scorecard, a tool created by the Rights of Way Habitat Working Group with the help of experts including ecologists, foresters, researchers and sustainability professionals. It encourages collaboration among those involved in developing and managing energy and transportation lands. Its metrics assess the quality of a habitat, identify threats and opportunities, and show how to improve management for the future by understanding how management affects pollinator habitat quality.

By including land use managers throughout the development process, and by considering the end land-use goal from the start, solar panel site developers and managers can plan for the long-term success of the site.

To learn more about the solar site development and the role of vegetation management, you can watch Corteva’s “Beyond the Panels” solar site management webinars here:

Sharing innovative research, success stories and tips with invasive plant managers.